On Saturday night I played horn in a pops concert with the Fremont Symphony that featured a medley of tunes from The Music Man. I played a gig with the Golden Gate Park Band on Sunday, subbing on fourth trumpet for a real trumpet player friend of mine, Daniel Gianola-Norris. I don’t play in bands that often, and when I do, it brings black a flood of memories. That I was playing trumpet this time meant that those memories focused around Bill McDonald, and I got to thinking about how he was the Professor Harold Hill of Grafton, North Dakota.

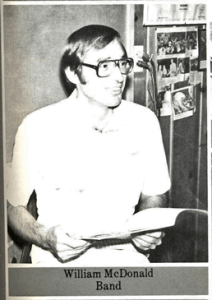

Grafton was a band town, and Bill McDonald was The Music Man of Grafton—the huckster-turned-hero, not courting Marian the librarian but married to Carole the special-ed tutor. Mr McDonald wasn’t the con man Prof Harold Hill starts out as in the musical, but the role of small-town band director requires all the rest of the role, from hucksterism to real leadership. Selling fifth graders on the joys of working really hard to sound like crap and their parents on spending lots of money on rent-to-own instruments is the huckster part. Shaping an army of kids from fifth through twelfth grades into bands that play concerts, swing, march, and serve a small town is a leadership task of heroic proportion.

Grafton was a band town, and Bill McDonald was The Music Man of Grafton—the huckster-turned-hero, not courting Marian the librarian but married to Carole the special-ed tutor. Mr McDonald wasn’t the con man Prof Harold Hill starts out as in the musical, but the role of small-town band director requires all the rest of the role, from hucksterism to real leadership. Selling fifth graders on the joys of working really hard to sound like crap and their parents on spending lots of money on rent-to-own instruments is the huckster part. Shaping an army of kids from fifth through twelfth grades into bands that play concerts, swing, march, and serve a small town is a leadership task of heroic proportion.

We had a concert each spring when the high school concert band and stage band performed along with the junior high and grade school bands, but nobody paid much attention to those concerts. In Grafton the purpose of a band wasn’t about music, it was about community, and the band season started on Memorial Day, with a modest, dignified ceremony at the American Legion Hall. The high school band played the national anthem and a few marches for the veterans in what still remained or fit of their old uniforms, along with much of the rest of the community, filling rows and rows of folding chairs. Everyone would stare solemnly at the fading, tattered flag at the head of the room, and the veterans tried not to reveal a moist eye when the roll of fallen heroes was called one more time.

The band season continued with summer marching band. I don’t recall if it was mandatory, exactly, but it was at least a moral imperative for high school band members to show up two evenings a week for summer band rehearsals. “High school” was taken loosely, too; Dave Christianson, Tim LaBerge, and I all joined the “high school” band before 7th grade, like Richard Schultz z”l did a few years later.

The first few rehearsals took place in the band room, which was the basement of a condemned Catholic Church that had been taken over by the overcrowded high school. That musty old dungeon was filled with the smells of valve oil, mothballed band uniforms, and pigeon shit. We’d play through the tunes for the summer—a folder full mostly of Sousa marches and a few two-page “overtures” or show tune medleys.

After that, summer band rehearsals took place on the neighborhood streets as we practiced marching. Grafton was a small enough town that special arrangements like police barricades weren’t needed; people just knew that on Mondays and Thursdays, if you were driving around the neighborhood of the high school, you might have to pull over and wait for the band to turn the corner. Did I mention it was hot, and that in the evening, the mosquitos came out? We’d be schlepping around in shorts and t-shirts, scuffing our sneakers into the pavement for each step—it took me at least two such evenings to figure out that the only way to slow your walk to a steady marching rhythm of 132 beats per minute that doesn’t bounce too much for you to play a brass instrument is to drive the shoe toe-first into the street—and trying to swat mosquitos, play our horns, and stay in tidy lines all at once, sweat dripping down the whole time.

Our director, Bill McDonald would start out marching on the left outside front row, next to the first of six trombones (this Music Man was 70 trombones short), every so often giving a few short tweets on his whistle. Those tweets presumably told the drummers what to do, but I wouldn’t know. Then he’d slow down and let the band get ahead as he slipped back a row at a time, tweeting and shouting at us to watch our diagonals and our “lineal lines.” Whatever those were.

And that is how I learned to do parade marching—by not knowing what the heck was going on and just doing my best to blend in. As far as I know, it’s how everyone learned. So when “Professor” Harold Hill teaches an entire small-town band to do something he hasn’t a clue how to do himself—play music—by giving them a fancy line about “the Think system,” he’s not actually that far off. Most bands actually do learn this way—by jumping in. Sink or swim, think and march.

Whistles happened, and the band started moving. I never figured out which whistle was which; I just did what everyone else was doing. Meanwhile, the drummers kept a steady cadence when we weren’t playing, and eventually I figured out which beats of the cadence required a little swing of the horn. At some point, Mr McDonald would tweet , the drummers would switch to a different pattern, and our feet knew to halt. I nearly fell over the first time, since I didn’t know it was coming. More tweets, drums resume, tweet, march, tweet, fold out the lines, tweet, fold in the lines.

The reason for all this marching practice in summer band was that Grafton was one of those small farming towns with a big spring parade related to agriculture—ours was The Sugarbeet Festival. The band marched behind horses and ahead of massive farm implements (not the ideal sequence, if you ask me, but it’s an age-old tradition that marching bands have to do slaloms around horse pies). Filling out the parade were a procession of old cars, fire trucks, floats, and the usual assortment of public officials throwing candy from convertibles lent for the occasion by local car dealerships.

After the Festival, the summer band season continued with evening concerts on the square across from the town dairy. We sometimes got little cups of ice cream with the funny paper-wrapped wooden shovel-spoons after the program. I’m not sure why, but the whole town turned out for these concerts that recycled the same old marches, patriotic anthems, show tune medleys, and the occasional movie theme.

We got Augusts off, and then marching practice resumed with the beginning of school in the fall—we had to prepare half-time shows for the football games. I remember many a fall afternoon spent with other band geeks and Mr McDonald pacing off the playground next to the condemned church with measuring tape, bottle caps, hammer, nails, and a can of white spray paint. We were marking out a grid with white bottle-caps nailed into the ground every five yards.

Five yards, eight beats, eight steps, one figure, two bars of music.

Once you’ve learned to walk eight steps to five yards, you never forget. When I graduated from college, we walked across a large grassy lawn, and I noticed that there were faint white markings on the grass every eight steps or so. In an excited moment of recognition, I asked my fellow Bachelor of Music degree candidates if this lawn was by any chance a football field. Nobody had a clue.

Back to high school, the full half-time show for Homecoming lasted around twenty minutes, half a dozen 5-1/2″x7″ folio-sized tunes. We’d do smaller pieces of that show at the Friday night home games leading up to that. We spent most of the first two months of school practicing those four or five tunes, first in the band room and then marching around that godforsaken field every morning. It was nippy most of those 8am band periods in northeastern North Dakota, and for a klutz like me, playing an instrument while marching on frost-covered grass was hard enough without also having to play half a dozen tunes from memory and trying to learn when to go where and how.

Back to high school, the full half-time show for Homecoming lasted around twenty minutes, half a dozen 5-1/2″x7″ folio-sized tunes. We’d do smaller pieces of that show at the Friday night home games leading up to that. We spent most of the first two months of school practicing those four or five tunes, first in the band room and then marching around that godforsaken field every morning. It was nippy most of those 8am band periods in northeastern North Dakota, and for a klutz like me, playing an instrument while marching on frost-covered grass was hard enough without also having to play half a dozen tunes from memory and trying to learn when to go where and how.

After Homecoming, the concert band season began, so those 8am band periods found us in the pigeon dungeon working on full-size music for our spring concert. On Wednesdays most band kids had study hall and a few dozen of us had stage band rehearsal.

Once basketball season began, part of our rehearsal time was given over to pep band practice—back to the folio-sized tunes we’d read off lyres while playing from the bleachers at all the home games. All the home games? All the boys basketball games, anyway—somehow I don’t remember playing for any girls basketball games, and certainly not for any volleyball. Every game meant a handful of band stalwarts had to meet up with Mr McDonald at the dungeon an hour before the game to load all the percussion and large instruments into the back of his pickup, ride over to the Armory to set up before the game, and then break down, reload, ride back, and unload everything back into the dungeon after the game was over.

Hockey season meant still more pep band. We only played at the arena a few times—it was too cold, for one thing, but a bigger problem was that the hockey arena was always way too crowded. Hockey was Grafton’s real sport. When I was in eighth grade, the team from the itty-bitty town of 5000 took the state hockey championship, and people are still talking about it. School broke for half-hour pep rallies in the auditorium many times in the weeks leading up to that championship, and every one of those pep rallies found Mr McDonald and the band crowded up in the balcony, blasting and pounding away through drum cadences and fiery pop tunes like “Proud Mary” and “Joy to the World.”

Somewhere in between all these games, Mr McDonald found time to schlepp a dozen or so of us off for a day or two at a time to the Fall Festival in Grand Forks, district and state solo and ensemble contests held at different high school and college campuses each year, All-State in Bismarck, and the annual jazz band contest in Minot.

The end of the sports season brought us full-circle back to the spring concert, where Mr McDonald finally got to stand on the podium, conduct real music, and hand out award certificates and ribbons in a presentation that culminated with the vaunted John Philip Sousa Award—the duties you expect to have when you get a music education degree. But he was also serving as logistician extraordinaire, spending the entire day getting instruments, stands, chairs and other gear over to the Armory, and herding cats all night to get and keep the fifth grade, sixth grade, junior high, concert, and stages band all arranged, seated, and quiet on the Armory’s basketball floor all evening. Then he had to supervise band nerds in yet another long, multi-trip load-out to get all the gear back to the dungeon. Those two-hour concerts must have felt like running a marathon to Mr McDonald.

But we’re still not done with the many duties of The Music Man. He was also teaching group lessons to all those fifth- and sixth-grade beginners, and he was giving private lessons to at least a dozen or so of the best students.

I’m not sure how he fit all that into a school week, but one of his tricks was to save himself the trouble of walking to the teachers’ lounge. Since he had the pigeon dungeon all to himself, he set up his Mr Coffee in his office behind the rehearsal room, and he chain-smoked his way through all those lessons and during his car trips to the grade schools. Fortunately there was also a squalid bathroom way back in the scariest part of the dungeon, past the row of filing cabinets of crumbling music and behind the room filled with mothballed uniforms.

He also got us band nerds to take over the uniform management, be the music librarians, and even do some of the repairs and cleaning for the school’s beat-up old instruments. A handful of us earned so many “points” this way that we lettered in band even before reaching high school and eligibility to buy a lettermen’s jacket (I don’t know any band nerds that ever bothered to buy the jacket to go with the letter, though), so he had to come up with a series of pins to put on the letters. All these after-school activities meant that when the temperatures dropped below zero, he ended up giving a bunch of us rides home.

Perhaps the most brilliant of all his time-saving tricks was to recruit a few of us older band nerds to take on beginning students. That’s how I found myself teaching private lessons to two beginning trumpet players and a baritone player in eighth grade, before I’d even learned to play trumpet myself. Which is how I found myself learning that all the brass instruments are the same—that even though I’d never played them, I could take my young charges’ horns and demonstrate for them, just like Mr McDonald could do on every last instrument in the band—except that I didn’t have the coffee-and-cigarette breath that grossed out a thousand beginners over the course of his career.

Perhaps the most brilliant of all his time-saving tricks was to recruit a few of us older band nerds to take on beginning students. That’s how I found myself teaching private lessons to two beginning trumpet players and a baritone player in eighth grade, before I’d even learned to play trumpet myself. Which is how I found myself learning that all the brass instruments are the same—that even though I’d never played them, I could take my young charges’ horns and demonstrate for them, just like Mr McDonald could do on every last instrument in the band—except that I didn’t have the coffee-and-cigarette breath that grossed out a thousand beginners over the course of his career.

My own private horn lessons started only a month into fifth grade. He’d been reluctant to start a beginner on horn—he was of the “start ’em on trumpet and switch ’em to horn a few years later” school—but that news sent me crying home from school. Several discreet phone negotiations later, my parents had secured Mr McDonald’s reluctant agreement to give me a chance starting out on horn, as long as I agreed to try again on trumpet when it didn’t work out.

I was the über-nerd horn prodigy who left the trumpet class in the dust, so instead Mr McDonald had to take me on as yet another private lesson student after classes. A few years later, though, he said that he had nothing left to teach me and set me up with private lessons at the University of North Dakota forty miles away. For the next several years, he modestly gave my university teachers all the credit for my progress—but I think plenty of credit goes to the guy who could put pride aside and see to it that I left his tutelage.

And we’re still not done with the duties of The Music Man.

Somehow the Grafton High School course catalog had an Advanced Music Theory course leftover from forgotten times, but one year, three of us band nerds actually signed up for it, so the administrator decided to find somebody to teach the class. It had to be either Peggy Bartunek, the general music and chorus teacher, or Mr McDonald, and I guess he lost the coin toss. He scheduled yet another after-school slot to teach the three of us out of a college freshman music theory textbook, and since we learned fast, he changed it from one day a week to three. By the end of that year (it was supposed to be a semester), he had the three of us writing four-part harmony, correcting each other’s work, and playing the results for each other on the electronic keyboard that sat nearby for stage band. Hunting down parallel fifths, parallel octaves, and voicing errors with Becky Tegtmeier, Melanie Kopperud, and Mr McDonald gave me harmony skills that still serve me to this day.

One year, Mr McDonald took small-town heroism to a whole new level, leading the Grafton High School Band on a trip to Washington, D.C., for the Cherry Blossom Festival parade and band contest. After a full year of fundraisers (which included selling more fruitcake than I ever want to see again in my life), we made our budget. That January found us outside on the weekends, holding marching practice in below-zero temperatures on ice-covered streets. We figured out how to play our instruments with mittens and gloves and arms stiffened by multiple sweaters layered under our parkas. Brass players had to use vodka instead of valve oil and trombone-slide oil, which froze. I remember dipping my trumpet mouthpiece in candle wax so that it wouldn’t freeze onto my face.

A few months later, we piled into two school buses for a long trip that lasted through two full days and nights with innumerable stops at Howard Johnsons, endless card games (penny a point), charades, and all manner of juvenile mischief. We spent most of a week piled six to a room in a cheesy motel, wearing matching blue windbreakers (so embarrassing), and keeping up a full schedule of sightseeing, band contests, parade practice, and finally the big parade. Then we turned back around for another forty-eight-hour bus odyssey home.

The band going to Washington, DC was the biggest news in Grafton since decades before when Joe Birkeland, another Prof Harold Hill type, took the band to the Rose Bowl Parade. A big gathering was organized at the Armory for the whole community to see the pictures, hear the contest recordings, and watch the videotapes made by one of the band parents who’d chaperoned—including a segment that records the supremely embarrassing moment I dropped a plate of nibbles and sent a slice of ham flinging onto the dress shoe of the aging “junior” US Senator from North Dakota, the Honorable Quentin N Burdick. We’d been invited to a reception at his office in honor of a sister of two of the band members’ being the North Dakota Princess for the Cherry Blossom beauty pageant.

The band going to Washington, DC was the biggest news in Grafton since decades before when Joe Birkeland, another Prof Harold Hill type, took the band to the Rose Bowl Parade. A big gathering was organized at the Armory for the whole community to see the pictures, hear the contest recordings, and watch the videotapes made by one of the band parents who’d chaperoned—including a segment that records the supremely embarrassing moment I dropped a plate of nibbles and sent a slice of ham flinging onto the dress shoe of the aging “junior” US Senator from North Dakota, the Honorable Quentin N Burdick. We’d been invited to a reception at his office in honor of a sister of two of the band members’ being the North Dakota Princess for the Cherry Blossom beauty pageant.

With exhausting band trips and an absurd heap of responsibilities like this, I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that he eventually burned out and retired from teaching. My sophomore year was his last as The Music Man. After that he put his inner huckster to work as a car salesman for several years.

And then all those years of chain-smoking his way through a ridiculous job caught up with him. His lung cancer spread fast, and he died some number of horrible months later. My mom worked at the hospital, and she happened to visit with him on the day that he died. The cancer had made it to his brain by then, and he was on a ventilator. His misery must have been acute, but somehow he managed to ask Mom how I was making out as a music major at college, and to speak to her with pride in his fading eyes about how I’d made him eat his words about not starting beginners out on french horn.

The Catholic church in town—the one that replaced the one with the pigeon dungeon—was crammed the day of his funeral.

A kaddish for Bill McDonald, The Music Man of Grafton and a number of communities before that. A kaddish for the guy who finally taught me trumpet for marching band several years after starting me on horn against his better judgment. A kaddish for the guy who led a whole community through its seasons for six long, exhausting years. A kaddish for the guy who on his deathbed could still be proud of a long-ago student.

Comments on Facebook:

Denise Prine Krumwiede Awesome! I was not musically inclined and he wanted me to play trombone to start with and well… He was a neat man!

Pam Peterson Fisher What a lot of work he put in to our halftime Homecoming shows. And, we learned a new song every year for marching band, unlike other schools who play the same song year after year.

Jennifer Holt Enriquez I’m kind of speechless. This is a remarkable essay.

Melanie Kopperud Backes Erin, Pitch perfect. Thank you for bringing back precious memories. What I learned from Mr. McDonald in our theory class served me so well through my B.S. in Music. And I can’t ever hear Proud Mary without thinking of Mr. McDonald.

Tim Hines Great Job!!! The cigarette and coffee breath line made me laugh out loud! (and I had to live with that, not one just an hour or so a day….)

Graftonites Reunite Yes, thank you Erin! It was almost as if I could smell the pigeon shit all over again and now thanks to you tim, I can smell the coffee and the smoke too! What a wonderful story about a wonderful teacher who made such a difference in so many young graftonites lives! I never played the drums myself but if I ever get around a snare I cant help but tap out 1 e and a 2 e and a 3 e and a TAP !

Tim LaBerge I think I still have nerve damage from the 8AM frostbite marching practices…

Carla Durand I can still feel my trumpet mouthpiece freezing to my lips. And the summer sweat rolling down my face, as we were all wrapped-up in wool uniforms in 90 degree weather.

Teri Burnham A remarkable tribute–funny and poignant. Thank you.

A note: Mr McDonald was Tim Hines’ and Teri Burnham’s step-dad.

Erin, What a wonderful tribute you’ve written for Mr. McDonald. I wish he was here to read it. You’re writing is so vivid that it brought back many wonderful memories for me. Bill McDonald gave so much of his time and talent for so many of us. It’s easy to understand why band directors have a high burn out rate.

Thanks, Amy Jo! Band directors, librarians, community theater directors—they’re all amazing small-town heroes.

Never having a musical thought in my mind except for the coming of Rock & Roll my whole Childhood revolved coming to town Fri. & Sat. nite to listen to Joe’s Marching Band. It was a real privilege to hold the music for one of the musicians.

I was the Chamber Photographer for Grafton’s 100th Anniversary & one of my highlights was shooting the Marching Band in all their finery. Steve Larson & I showed the slide show at that Fall Chamber Bqt & received standing ovation. The part of the Band was the highlite of the show with the Music picked by Steve. I had one good shot of Joe with a tear coming down one cheek and Steve added, “The Leader of the Band”. This was before Digital & We had 3 slide projectors & We both held our breaths as the 1st slide came on the screen & the other 2 projectors followed in perfect harmony.

Not to mention any names But one Businessman who I shall not name but never seemed to like anything came up to me after the finish & said, I usually would like to sneak out before any of these programs but that was pretty good.

When the Program was over the slides were supposedly taken to the Chamber Office never to be seen again. I always wanted to make a print of Joe framed by one of those big Horns “Don’t know what it’s called” with the tear coming down but Alas I had not yet made dups so the program is gone forever.

Bill Kingsbury.